2. The Path of Allah

Shortly after returning from Egypt, I was determined to immerse myself in the study of Islam and Arabic.

The awakening of my own faith seemed to coincide with a general Islamic awakening in the world around me during the late 70s and early 80s. I don’t know whether this rise in Islamic awareness was prompted by events at the time but many second generation Muslims in the UK were beginning to re-discover the religion of their birth, after a long period of having been Muslim only in name. There was an air of excitement and dynamism about the Muslim community, particularly in London. Study circles and informal gatherings sprang up in living rooms or community centres. Each Friday, the display window in the foyer of Regent’s Park Mosque seemed to get ever more packed with little cards announcing new events. Even greeting someone with Salams after prayers usually prompted an invitation to a Zikr (Remembrance of Allah) or a Halaqa (Islamic Discussion Circle). When I took part in such meetings I was struck by the diversity of those attending: Asians, Europeans, Africans, Turks, Kurds, Arabs, Malaysians and Iranians. They came from all walks of life: civil servants, students, bus drivers, doctors and parking attendants. There was no barrier of race, class or nationality. Being a Muslim was the only thing that mattered and it granted instant membership of the Ummah (community). The aim of the Islamic meetings was to learn about Islam, but equally important was the social side – getting to know other Muslims in the area and building up a sense of brotherhood. Gradually these meetings spawned other meetings catering to the needs of a particular locality, ethnic group or interest.

The first meeting I began attending in 1980 was “The Islamic Society of the Faithful”, held alternately in the living rooms of Brother Shafiq or Brother Azim, both Asians from East Africa and elders of the local community. Most of us who attended were born Muslims but had not been practising and so there was a sense of discovery and learning. We started going through the basics of what were the beliefs and practises of Islam. In those days there was none of the sectarian or other divisions that became apparent later, none of the dogmatic insistence on this or that point of Islamic faith. The meetings were broad-minded and inclusive. I also enjoyed these meetings because of the wonderful food we had at the end of them. Na’eema, Shafiq’s wife, would serve us Moroccan cous cous, Lebanese stuffed vegetables or Turkish kofta, while Khaira, Azim’s wife, would present us with biriyani, curry and samosas. I loved the sense of belonging and identity this gave me. It was like being part of a huge family that shared a special bond.

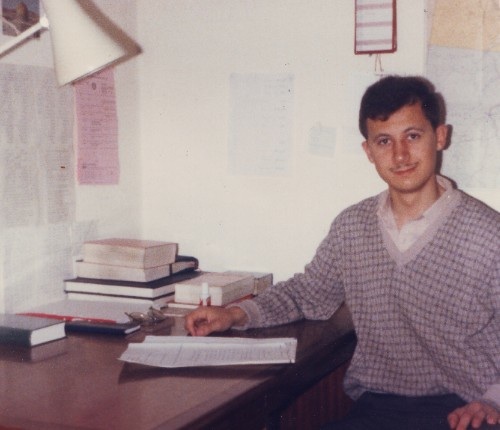

One thing that came out of the meetings of “The Islamic Society of the Faithful” and from discussions with almost every Muslim I met was the importance of learning Arabic, the language of the Qur’an. I knew it was an essential step towards truly understanding Islam. I also felt it was my duty to learn Arabic since it was part of my heritage and identity. I enrolled for a degree in Arabic and Islamic Studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). My tutor was David Cowan, the author of “Modern Literary Arabic”, an elderly but sprightly Scotsman who converted to Islam in his youth. Also at SOAS at the time were Dr. Wansbrough and Dr. Cook, the Salman Rushdies of their day. They had both recently published books that undermined the Qur’an’s claims to divine authorship, Wansbrough asserting that the Qur’an was a product of various sources, improved and perfected through oral narration after Muhammad, and Dr. Cook, along with Patricia Crone, claiming that Islam began as a variant form of Judaism and only much later developed into a separate religion. Neither book engendered much of an outcry. Today, such criticism of Islam would undoubtedly spark worldwide demonstrations, but the Muslim community in the late 70s and early 80s was not yet politicised. The radical groups that exist today were only just getting started in the UK and had yet to spread their influence. As a young Muslim keen to soak up everything I could about Islam, I found the atmosphere at SOAS invigorating, and I attended every extra-curricular lecture and debate. I also couldn’t stop reading anything and everything that had Islam as its subject matter, and the SOAS Library became my second home. I stayed there studying until late into the night and regularly had to be asked to leave by staff locking up.

In between my own efforts to learn more about Islam, I was also busy spreading the word to others and, in particular, to members of my own family who were not practicing. I was motivated by an ardent desire to share what I had discovered and to save them from hell-fire. My two eldest sisters were already devout Muslims, but the rest of my family was not. It was my Islamic duty to give them ‘Da’wa’, which literally means ‘invitation’. I had recently seen the film “The Message” about the life of Prophet Muhammad. It begins dramatically, with three masked horsemen galloping across the desert until they arrive at the courts of the rulers of Byzantium, Persia and Egypt, to deliver letters inviting them to Islam. This is the letter to Heraclius, the Byzantine Emperor:

In the name of God, the Beneficent the Merciful. I call you to Islam. Accept Islam and you will be safe and Allah will give you a double reward in this life and in the next. If you do not, you will have to face the consequences.

Seal; Prophet Muhammad

‘OK,’ I thought to myself, ‘if that’s how the Prophet did it, then that’s how I’ll do it.’

Dear Evette,

I call you to Islam. Accept Islam and you will be safe and Allah will give you a double reward in this life and in the next. If you do not, you will have to face the consequences.

Love, Hassan.

I don’t know how Evette reacted to that letter, for she never said anything. I decided to change tactics and focus on one-to-one discussions. I started with my younger siblings. I spent a great deal of time reading verses of the Qur’an and discussing their meaning.

Regents Park Mosque.

One day I was visiting brother Shafiq, when he suggested accompanying him on a “Tablighi Jamaat.” Tablighi Jamaat was a movement that started in India by Muhammad Kandhalawi who wanted to bring Muslims back to the path of pure Islam. They adhere to the Deobandi brand of Sunni Islam that is followed in large parts of South East Asia and has a huge following in Pakistan and India. During the 80s the group had become very popular in the UK.

“What’s Tablighi Jamaat?” I asked.

“It’s a gathering where they give talks about Islam. Why don’t you come?”

“Where is it?”

“Dewsbury.”

“Where’s Dewsbury?”

“Near Leeds.”

“Leeds? That’s miles away!”

“Oh, it won’t take long. Come on – you’ll learn a lot and really benefit from it.”

Before I knew what had happened I found myself on a long road trip heading to Yorkshire. After making a couple of stops to pick up some brothers, we arrived in the little town of Dewsbury nestled in the Yorkshire moors, with its quaint rows of Victorian terraced houses. It didn’t seem at all like a place where Muslims would be gathering to discuss Islam. But as we turned a corner I was confronted by a huge mosque at the end of the road. Even more incongruous was the sight of little Asian children in Pakistani traditional dress all along the street leading to the mosque, playing with toys on the cobblestones, while women in headscarves stood half emerged from doors that opened on to the pavement, chatting away in Urdu. If it wasn’t for the grey northern skies above us, I might have mistaken it for downtown Karachi.

The mosque in Dewsbury was still unfinished and there were bags of cement and sheets of plaster board stacked against breeze blocks, while the main floor space was interrupted by unfinished columns with wire mesh poking out. Health & Safety would have had a fit. The mosque was full and there were several lectures in progress. Most of the lectures were in Urdu, but I was taken to a gathering for English speakers. The Maulana leading this gathering was sitting on a raised platform and spoke in broken English to a mixed gathering of Arabs, Africans, Malaysians and Asians – who I assumed did not understand Urdu. On one side of me sat a chubby African man in a colourful Kaftan and decorative hat. He smiled and peered at me through his glasses that had such thick lenses his eyes seemed to be twice their actual size. Throughout the talk he continued to stare at me . I glanced over at him – frowning slightly, hoping he would see my irritation, but he only grinned and stared even more relentlessly.

“Are you Muslim?” he finally ventured.

“Yes,” I replied in a hushed tone, trying not to disturb the talk.

“Mashallah! (Whatever God Wills!) How long have you been a Muslim?”

I hesitated. I wasn’t sure what to say. Technically I was born a Muslim.

“Well I’ve been practising for about a year.”

“Do you know how to pray?”

“Yes.”

He thought I was a convert to Islam. I soon discovered that English or Western converts attract special attention from Muslims. It was partly a protective instinct to guide the uninitiated, to help new Muslims understand the basics. But another reason was the sense of inferiority that the age of European colonialism had left Muslims with. Subconsciously many Muslims still regarded their white European colonizers as superior beings. The fact that a white man or woman had converted to Islam was a special kind of proof that Islam was indeed true and such converts received a great deal of attention. I encountered this attitude often and found myself having to sit and listen to lectures on the most basic and obvious aspects of Islam. It felt extremely patronizing.

“My father is from Egypt; my mother is English.” It was a sentence I would have to use often.

“Is your mother Muslim?”

“Er… well… not really.”

“Oh, you must try and make her Muslim.”

“Yes… inshallah…”

“It is your duty to save your family from Hell Fire!”

“I hope you don’t mind if we talk about this later, brother. I want to listen to the talk.”

The Maulana was talking about death and the Day of Judgment.

“The prophet said, ‘When a dead person is carried to his grave, he is followed by three things. Two of them will return after his burial but one will remain with him. They are his relatives, his wealth, and his deeds.’” He paused.

“His relatives will go back and his wealth will be re-distributed!”

He opened his eyes wide, “But his deeds will remain with him.”

“Yes my dear brothers, our deeds are of utmost importance. It is only our deeds that will follow us to our grave. They will stay with us as we await Judgment and they will stand by us when we are questioned. They will then either speak for us or against us. It is then that we will realize the importance of even the smallest of actions. But it will be too late to return and make amends. No second chance!”

The Amir began extolling the virtues of Tabligh (spreading the word of Islam).

“What is more important than spending time in the path of Allah? Do we truly love Allah and his Prophet more than our own selves? Or are we too attached to the comforts and earthly pleasures of this world? Are we so weak in our faith that we cannot even afford to give even a little time in the service of our creator? All you have to do is make Niyyat (intention) for a couple of weeks or a month or a year!”

“What does he mean ‘make Niyyat for a year’?” I whispered to the young Malaysian student beside me.

“He means you must make intention to go with a ‘Jamaat’ (group) and invite others to Islam.”

“What?”

One by one those around me got up to go. Most had their rucksacks ready. Some were even clutching passports and plane tickets.

“I can’t go anywhere! I have to go home.”

But the Malaysian student had already got up to join a group heading for Newcastle.

I suppressed an urge to make a dash for the door and instead tried to think of an excuse. But after all the talk of the day of judgment and the importance of even the smallest of actions, every excuse I thought of just sounded like; ‘It’s OK, I don’t mind burning in hell.’ I stood up and looked around for Shafiq, but when I spotted him he just smiled and waved.

“See you in two weeks, Hassan!” he shouted, before exiting with a large group.

The Amir noticed me looking bewildered.

“Have you made intention brother?

“My family don’t know where I am.”

“You can phone them.”

“I have to go back home. I have things to do!”

“Isn’t spending time in the path of Allah more important?”

“Well… I suppose so… but how will I eat?”

“Food will be provided!”

“How will I sleep?”

“You will sleep in the Mosque!”

“What about my mum?”

“She will be fine!”

“What about…” The thought of gripping my leg, wincing in pain and complaining about an old war wound, crossed my mind briefly.

“Just make intention, and Allah will make a way for you!”

My intention was to go home, but God’s intention was obviously different and I found myself being directed to a delegation bound for Leeds. We filed out of the mosque and boarded a mini bus waiting outside.

I had never been to Leeds and consoled myself with the thought that at least I’d be visiting somewhere new. But apart from the mosque I saw very little of Leeds. For the next fourteen days we ate, slept and prayed in the mosque. I was given a sleeping bag and ill-fitting cotton Shalwar Kameez (long shirt and baggy trousers). At meal times long rolls of paper were laid down and curry and chapattis were provided, cooked in rotation by the members of our group, though they only gave me washing-up duty.

We were told not to discuss politics or areas of religious dispute. We were even discouraged from discussing the meaning of the Qur’an. On one occasion I was sitting with a brother, trying to explain some of the Arabic words to him, when I was told to stop.

“You shouldn’t give Tafseer (meaning of the Qur’an) unless you are a scholar,” said the brother. “Just learn by heart the Suras the Maulana taught us.”

“But then we’ll be reciting words we don’t understand?” I complained.

“It doesn’t matter. You will benefit from your recitation!”

I found it difficult to see how one could benefit from reciting words without understanding their meaning, but I soon learnt that the act itself was considered a form of worship that would confer blessings upon those who engaged in it. As a result memorization of the Qur’an without understanding it is very common amongst Muslims, particularly those from non-Arabic speaking countries. (Even those from Arabic speaking countries have problems understanding the archaic language of the Qur’an.) The majority of those with me in the Leeds Mosque were of Pakistani or Indian origin, and although they had memorized huge passages and in some cases the whole of the Qur’an, few could understand a word. Memorizing the Qur’an is not as difficult as it may seem. The language of the Qur’an has a poetic rhythm with repeated phrases and patterns, such as beginning a sentence with “Qul!” (Say!) or ending it with two adjectives of God. Certain stories about past prophets or parables about believers and unbelievers are re-visited throughout the Qur’an, so that a sequence one has already memorized will occur in a similar form elsewhere. Children are also taught to read the Qur’an from a very young age – as soon as they can imitate sounds in some cases – and families hold a celebration called a Khatam (completion) once their son or daughter has read the whole Qur’an. I memorized the last Juz’ (1/30th of the Qur’an), which are the short Suras (chapters) at the end of the Qur’an and which are most commonly used in daily prayers. I also learnt several other important Suras and verses such as the last three verses of al-Baqara and al Kahf and “The Verse of Throne” and Suras such as “Yaseen” and “Al-Rahman.” Fortunately my studies at SOAS helped me to learn the meaning of what I was memorizing.

There was one book we were encouraged to understand. It was called “The Teachings of Islam” by Maulana Zakarya Kandhlwi, a large volume badly printed on cheap paper and bound in a gaudy red plastic. We were all given our very own copy and told to study it when we were not engaged in prayers or listening to talks. This book was the source of many of the lectures I heard at the Dewsbury Mosque and over the coming days in Leeds. It related stories of the Prophet and his companions and quoted passages of the Qur’an. The emphasis was on reaching the utmost state of piety, abstinence and fear of God. At first I found many of the stories strange and disconnected from the society around me.

One story began with the heading “The Prophet Reprimands the companions for Laughing.” It read:

“Once the Prophet (peace be upon him) came to the Mosque for prayer where he noticed some people laughing and giggling. He remarked: ‘If you remembered your death I would not see you like this. Remember your death often. Not a single day passes when the grave does not call out: ‘I am a wilderness’ ‘I am a place of dust’ ‘I am a place of insects’. When a believer is laid in the grave it says; ‘Welcome to you. Very good of you to have come into me. Of all the people walking on the earth I liked you the best. Now that you have come into me, you will see how I entertain you.’ It then expands as far as the occupant can see. A door from Paradise is opened for him in the grave and through this door he gets the fresh and fragrant air of Paradise. But when an evil man is laid in the grave it says; ‘No word of welcome for you. Your coming into me is very bad for you. Of all the persons walking on earth I dislike you the most. Now that you have been made over to me, you will see how I treat you!’ It then closes upon him so much so that his ribs of one side penetrate into the ribs of the other. As many as 70 serpents are then set on him to keep biting him till the day of resurrection.”

The author explains the purpose of the book in the forward:

“Muslim mothers, while going to bed at night, instead of telling myths and fables to their children, may narrate to them such real and true tales of the golden age of Islam that may create in them an Islamic spirit of love and esteem for the Sahabah and thereby improve their faith and that it may be a useful substitute for the current story books.”

The more I read the more acclimatized I became to the mindset of seventh century Arabia. After several days of confinement in the mosque and a constant routine of talks, prayers and readings from this book, I was so immersed in the events of the early Muslims that I began to feel estranged from what I now regarded as the sinful world around me. But in spite of it’s sinfulness, the Amir regularly ordered expeditions to this very world. Each day he chose a group of three people to visit an address on a list collected by brothers beforehand. These addresses were those of local Muslims who for one reason or another were believed to be in need of “Da’wa” – in other words bringing back into the fold of Islam. I was a little anxious when finally chosen to join a group.

The Amir gave us very specific rules regarding our conduct outside. We were not to look around at all the Haram (forbidden) things around us. We were to keep our eyes lowered at the ground, a couple of yards ahead of us and repeat a little prayer to ourselves. This made it a little difficult to follow the directions, to negotiate busy streets and cross roads. Eventually we turned up un-announced at the house. A short clean shaven young Asian let us in and offered us some food and drink, which we politely turned down, as instructed beforehand, in case this reprobate had used forbidden ingredients such as gelatine, non-halal meat, or alcohol in his cooking. We sat gingerly on the edge of his sofa, as our leader – a leader of every group was always appointed – repeated the talks about death and the Day of Judgment and other stirring stories from the big red book. We beseeched the stray brother to come to the mosque to listen to our Amir. Eventually he agreed to join us for afternoon prayer. Mission accomplished, we carefully made our way back .

I began slipping into a very obsessive mindset. Even the most minute rituals and practices of the Prophet took on extraordinary and exaggerated importance that must be followed if I was to avoid the fires of Hell, while all other matters of life seemed irrelevant.

“We should never think we are in any way more advanced than the Prophet was,” said the Amir. “Everything he did was the best example for us. Even when we travel by car or plane we should remember that travelling by camel or donkey is better, because that is the way the Prophet did it.”

Copying the Prophet included the way we brushed our teeth, and our Amir gave us a talk about the importance of using the Miswak, a twig from a type of tree found in the Middle East. He related the saying of the Prophet;

“Was it not for my fear of imposing a difficulty on my nation I would have ordered that the Miswak be used before every prayer.”

He then produced a Miswak and demonstrated how it should be used, stripping off the bark from the tip and chewing it until it was frayed. He then rubbed it against his teeth from side to side. When he had finished he told us a story from the time of Omar, the second Caliph of Islam.

“During the conquest of Egypt, the Muslim army was having great difficulty in defeating the enemy. When Omar heard of this he said it must be because of a deed they have committed. So the Muslim fighters asked themselves if they were neglecting any religious duty, but they found they were not. Then they asked themselves if they had neglected any Sunnah (practice of the Prophet) and they discovered that they had forgotten to brush their teeth using the Miswak. So they got together and started using the Miswak. Once the enemy saw this they thought the Muslims were preparing to eat them alive and fled.”

Every second of my day was now controlled and defined by this or that Sunnah. When going to the toilet I was taught to clean myself in a certain way and utter a prayer when entering and leaving the toilet. Islam even regulated the way I slept, and on my second night I was rebuked by the Amir for sleeping the wrong way. He explained that a Muslim should never sleep with his feet pointing towards Mecca but should always sleep facing it. I wasn’t quite sure if he meant only that my head should be pointing towards Mecca or whether I should be literally facing Mecca. To be on the safe side I kept my face in the direction of Mecca and prevented myself from turning side to side as I normally did, which made it very uncomfortable and difficult to sleep.

I became increasingly concerned that such a high level of attention to form and detail was not sustainable outside the sheltered environment of the mosque and worried about my salvation if I was unable to maintain it. But it was difficult to voice this concern in an atmosphere where group mentality strongly disapproved of any failure to live up to the standards set. The Maulana seemed to take pride in how hard and difficult it was to practise Islam properly and said that Prophet Muhammad had said:

“A time will come upon people wherein the one steadfast to his religion will be like one holding a burning coal.”

The sheikh explained that in this day and age to be a good Muslim is like clasping hold of a red hot piece of coal. One instinctively wants to throw it away, but one must resist the instinct and grab it tightly if one wants to achieve Paradise and avoid Hell. A ‘true’ Muslim had to sacrifice the comforts and pleasures of the world for austerity and hardship if he was to gain the comforts and pleasures of paradise. He must expect to be thought of as a weird and strange by non-Muslims and suffer ridicule from the society around him, as the prophet said:

“Islam began as something strange, and it will revert to being strange as it was in the beginning, so good tidings for the strangers.” Someone asked, “Who are the strangers?” The Prophet replied, “The ones who break away from their people for the sake of Islam.”

Although I had only been at the mosque in Leeds for two weeks, it seemed much longer, and when we got back to Dewsbury I felt disoriented and apprehensive about returning to ‘the real world’ with its evil temptations ready to entice me away from God. I looked for Shafiq, but he hadn’t returned. It was during Ramadan, and we had been fasting all day. At sunset everyone broke their fast together in Dewsbury mosque. I was starving, and the curry and chapattis never tasted so good.

As soon as we had finished eating the talks started up again. I decided to nip outside for some fresh air. When I got outside I saw there were about fifteen or twenty men standing in a long line around the back wall of the mosque. They had all sneaked outside to have a quiet cigarette. This was their first cigarette after a long day of fasting and many were dizzy from the sudden nicotine rush, and as a result they slurred their ‘Salams’ as they glanced at me sheepishly with glazed eyes. Although I had been a smoker myself not so long ago, I now felt it was very ‘un-Islamic’ and I strongly disapproved. The fact that many had long beards and large turbans increased my indignation. But at the same time there was a part of me that seemed to take comfort in the fact that there were practicing Muslims who were less than perfect. It made me feel better about the possibility that I might fall short of being a ‘perfect Muslim’ myself.

I was delighted to finally see Shafiq the next day. I wanted to know if he had been through a similar experience as me and whether he too felt worried about some of the things he had heard. But he looked relaxed and un-phased by his experiences and told me how wonderful it had been and how he could not wait to go out on his next Jamaat. I was relieved to get back home. I felt a little nervous. Things looked different. My priorities had shifted. I was less concerned about this life and far more focused on the next life. I grew my beard, wore a long white Jilbab and cap. I not only prayed all the compulsory prayers, but I prayed all the extra prayers, too. I began fasting every Monday and, of course, always brushed my teeth with a Miswak. I was also determined to keep in my mind that heightened state of fear of God that I had felt in the mosque. My friends and family were at first a little surprised by the even more devoutly religious Hassan, and humoured my somewhat obsessive attention to every tiny detail of Islam. However I soon found that being back in the ‘real world’ gave me a more balanced perspective and the sense of anxiety and fear gradually subsided as I realised that Jamaatu Tableegh’s obsession with form and ritual was a distorted perception of Islam. I came to appreciate what the Qur’an said, that “God does not task a soul beyond what it can bear,” and that the needs of this world and the needs of the next world did not have to be in conflict. I began to seek a more sophisticated and deeper appreciation of Islam than Jamaatu-Tableegh offered.

Hi, I enjoyed reading this chapter.

Gives people an idea of what is going on at the end of their street.

Thank you very much for this. This is the only detailed description of “Tablighi Jamaat” that I’ve ever read. The contrast between your initial joy at discovering a new passion and the sense of unity and identity it gave you, with this obsessive, introspective version of Islam is startling and very revealing. I’m looking forward to reading the rest of this blog.

-Do you recommend reading “Quranic Studies” by John Wansbrough or any other of his books?

-“If you do not, you will have to face the consequences” – Doesn’t this contradict the verse that says one shouldn’t force religion on others? plus is this evidence that islam spread by force?

-I find it disgusting how some religious scholars use fear and talks about eternal torture in hell as the first means of grabbing youths attention.

-“We were told not to discuss politics or areas of religious dispute.” – this is typical in such “unsophisticated” not well educated “salafy” groups. It is their childish way of cutting down the questions and doubts.

-“they had memorized huge passages and in some cases the whole of the Qur’an, few could understand a word.” this is very common even among Arabs. In fact most of those that have memorized the entire Quran have never read the tafseer not even a couple of pages of it. Even after they are done memorizing it they are told by their teachers to revise it again and again and again. Why? Because apparently forgetting it after memorizing it is a very bad sin. But how about reading a tafsir just for once???

-“I began slipping into a very obsessive mindset.” that is typical too. Most converts and newly devout muslims do that.

Thanks for writing your story, the gentle and careful way it is written is refreshing.

THANKS FO PUTTING IN YOUR OPINION OF TABIGHI JAMAAT. i MYSELF WENT ON JAMMAT FOR A WHILE. THE BROTHERS I WENT WITH WERENT SO HARSH THOUGH!

I remember Tablighi Jamaat visiting my house in the mid 90’s. One member was telling me how he used to go night clubbing and womanising but now he has come on the straight path, and advised me to do the same. I kept thinking, “I’ve never been to a night club or even had a girlfriend so what makes this guy think I’m not on a straight path? Just because I don’t dress like them or go to the mosque obsessively and I frequently lapse in my prayers. I started getting the feeling that it was more about ultra-conformity and even a form of mind control”.

I’m discovering new things through your blog. I thought I’d try to learn more about Islam this Holy month of Ramadan. But the more I look I discover things that make me question things more and more.

I am watching Islamic channels like peace TV and Ramadan TV. The fear of death and hell and strict adherence to sunna are laid on thick these days.

The channels also tell of the compassion and humanity of the Prophet (S.A). After reading about the letter to Heraclius, I started thinking to myself history really is written by the victors.

السلام عليكم ورحمة الله وبركاته

Brother in Islam,

It was refreshing to find your blog post. Most of what you described is very common in Tableegh work. Experiencing those things we previously didn’t know, self-doubts, questions, and then returning to encounter the doldrums of our dunya duties.

What is significant is that the effort to bring Islam into one’s life is a lifelong effort. In order for us to become a means of guidance for others, we must become guided ourselves. That requires much work and attention.

When one returns after khurooj, one SHOULD be struck by the desire to continue the practices learned, the seeming meaninglessness of our mundane matters, and then the usual decline in our Iman and practice as we become re-consumed by the material environment. That is the purpose of continuing the effort – it must be on-going or we run out of gas and will never continue our own growth and development.

It was a real pleasure to hear your story. May Allah help you and all of us to strive the rest of our lives until the Deen enters us completely, the Help of Allah comes to our rescue, and humanity witnesses the grandeur of Real Islam again ! Ameen.

By practicing Sunnah and calling humanity towards Allah, the good among humanity will be drawn toward the Truth, and the evil ones will be filled with fear and awe, insha Allah !